The last few months have seen me form a close relationship with Expressionist films. Especially the early films of the movement. Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr Caligari made for some ideal Halloween viewing.

The silent era can often make it difficult to discern the differences in European and American cinema when the evident language differences cannot be relied on. Metropolis has more in common with a high budget Hollywood production than it does the grainy reputation of Expressionist film, but was of course created by German Filmmaker Fritz Lang.

The Two Models:

By the 1920’s Hollywood had developed its filmmaking model into an exact science and produced commercially successful films at the rate of which Henry Ford was producing cars (as described by Grievson and Kramer).

Hollywood worked within a centralised unit and from their California studios operated by strict laws written up by producers to ensure that only the most moral of Christian ethics were shown on screen. Though more important to Hollywood was not the pursuit of morality, but the far more important pursuit of money.

Genre films were the best sellers! Slapstick comedies by Laurel & Hardy were major sellers, as were the action packed films of John Ford. Films with a traditional narrative structure that focused on Characters, usually figures of bravery or of comedy and usually played by famous faces that the public were taking a greater interest in. Hollywood was the home of the movie star as well as the cash machine that films had become.

Meanwhile across the Atlantic; Weimar cinema was trying to find its way in a market that was saturated. While the First World War had blocked imports of American films, ensuring the security of German films, studios now had to carve their own place in what was becoming an increasingly globalised industry.

Eventually some innovative characters decided “Instead of making films for money, why don’t we make films for the sake of making films” and thus born was “Films for Art” and with it The Expressionist Movement. While still commercially successful their place in history was solidified not by financial success but instead their landmark significance as works of fine art.

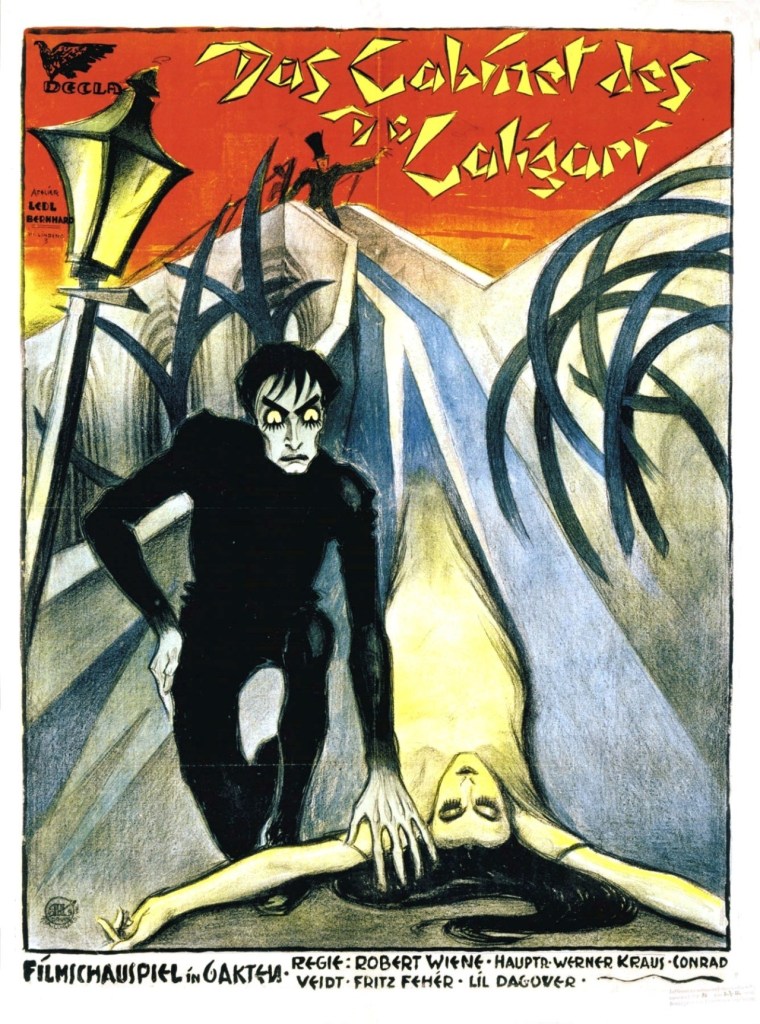

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari:

(Watch Here)

This rather chilling murder mystery tells the story of a society being harassed by sleepwalking murderer, controlled by the deranged Dr Caligari broke most of the rules of conventional cinema of the time. Set designs were surreal, the ending was twisted and the film makes extensive use of Chiaroscuro lighting. The film is pure murder and mayhem. While now the film industry boasts an large range of such films, this was the first of its kind.

Inspired by expressionist paintings Robert Wiene and writers Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz used the violent imagery of the film to explore the issues of the day, most notably the suffering caused by the recently ended war.

The most notable Hollywood rule broken by Wiene was the use of narrative structure, the story within a story model (while common place today) was unheard off, lest the audience be confused or maybe just forget they were watching a film altogether! Because its not like they’re capable of independent thought?

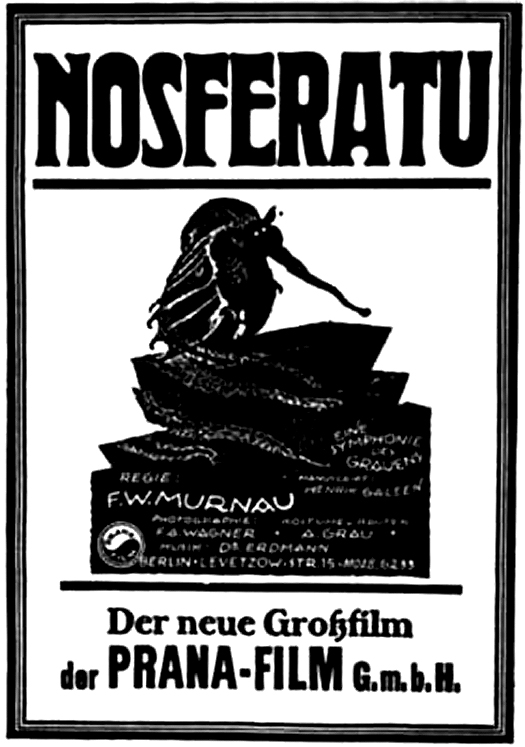

Nosferatu:

(Watch Here)

The first movie monster took the form of discounted, unofficial Dracula imitation Count Orlok. The creepy uncle of villains. Shot on location in the villages that time had forgotten; Nosferatu used similar rebellious filmmaking methods to tell the story of the bloodthirsty count. Its use of shadows and lighting unsettles the audience. The sinister and macabre tones of the film completely set it apart from Hollywood who wanted audiences to feel good watching a film, they were of course unaware how much money horror films would make in the not so distant future.

The film also unconsciously explores ideas like repressed sexuality, a reflection of director F.W Murnau’s own homosexuality which was illegal in the 1920’s. Such controversial themes would not be explored by Hollywood for many years.

Metropolis:

(Watch Here)

Metropolis made in the late 1920’s has much more in common with a large budget Hollywood production. The elaborate set design and extensive use of special effects work together to create what would go on to become the Science Fiction Genre; inspiring films like Blade Runner.

While not as eerie as Nosferatu or as unsettling as The Cabinet of Dr Caligari; Metropolis was still in many ways at odds with Hollywood, American studios making extensive cuts before releasing the film to the US Market.

Like its predecessors in the expressionist movement Metropolis was heavily influenced by artistic movements such as Cubism and Futurism. It explored the emerging issues of the time such as Communism and Fascism as well as Industrialisation and Mass Production, specifically the effect that it had on workers; the working life of whom had gotten increasingly difficult as a result.

The Great Merger:

It is notable however that in many ways Expressionist films were not so different to their Hollywood counterparts, as much as Fritz Lang may have argued for that case.

While the focus on German cinema was artistic movement, it was still a commercial venture. Films are created to make money (or as a tax write off). Weimar Cinema did not change that. Likewise the filmmakers Lang and Murnau went on to develop successful Hollywood careers, bringing with them their insights into the craft.

Hollywood would emulate their success in the Horror and Noir and Science Fiction genres, incorporating art cinema into their Fordist Production Machine. Who would continue to thrive as Weimar cinema died with the rise of well known shit biscuit Adolf Hitler.

The lessons learned from expressionist films are what gave us Hitchcock’s Thrillers, Siodmak’s Neo Noir detective film and even went on to inspire the early Superhero films.

I had the pleasure of doing a short presentation on this subject for my Film History Class, so if you want to watch me be awkward and earn myself a poor grade in real time, you can watch it here.

Bibliography:

•Cook P, (2007) The Cinema Book, Third Edition, British Film Institute. •Burch, N, (1990) Life ToThose Shadows, BFI Publishing •Gunning T, (2006) The Cinema of Attraction: Early Film, Its Sepctator, and the Avant-Garde in Strauven W (ed) Cinema of Attractions Reloaded) Amsterdam University Press. •Kaes A, (2004) Weimar Cinema: The Predicament of Modernity, in Ezra E (ed) European Cinema, Oxford University Press. •Kracauer S, (1947) Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, Princeton University Press. •Thompson K & Bordwell D, (2019), Film History: An Introduction, Fourth Edition, McGraw Hill Education. •Grieveson L, Kramer P, (2003) The Silent Cinema Reader, Routledge. •Freud, S, (2004), The Uncanny in Sandner D, Fantastic Literature: A Critical Reader • •Bordwell, David. “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” Film Criticism, vol. 4, no. 1, 1979, pp. 56–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44018650. Accessed 8 Nov. 2020. •Cardullo, Bert. “Expressionism and the Real ‘Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.’” Film Criticism, vol. 6, no. 2, 1982, pp. 28–34. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44018696. Accessed 8 Nov. 2020. •“SIGNS AND MEANINGS.” Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, by Cristina Massaccesi, Liverpool University Press, Leighton Buzzard, 2015, pp. 83–102. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv13841gj.9. Accessed 9 Nov. 2020.POLAN, DANA. Journal of Film and Video, vol. 38, no. 3/4, 1986, pp. 146–148. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20687746. Accessed 8 Nov. 2020.